Alfred Hitchcock was particularly fond of set pieces. He treated them as crescendos, eye-catching scenes built to demonstrate his virtuosity and break the viewer out of a trance. A properly paced film would include three of these "bumps," although Hitchcock enjoyed showing off more than average (I could consider Rope one long set piece).

Alfred Hitchcock was particularly fond of set pieces. He treated them as crescendos, eye-catching scenes built to demonstrate his virtuosity and break the viewer out of a trance. A properly paced film would include three of these "bumps," although Hitchcock enjoyed showing off more than average (I could consider Rope one long set piece).Another informative definition comes from screen writer John August, who defines a film set piece as:

A scene or sequence with escalated stakes and production values, as appropriate to the genre. For instance, in an action film, a set-piece might be a helicopter chase amid skyscrapers. In a musical, a set-piece might be a roller-blade dance number. In a high-concept comedy, a set piece might find the claustrophobic hero on an increasingly crowded bus, until he can’t take it anymore. Done right, set-pieces are moments you remember weeks after seeing a movie.

While some conventions are followed, others are discarded to set the scene apart. Game conventions should be treated similarly, altering the experience for a particular purpose. But if we were to follow Hitchcock's suggestion of three bumps per film, a twelve hour videogame should include eight or more set pieces. While rare in older titles, Uncharted 2 teems with cinematic set pieces and is representative of what I hope is a larger trend in game design.

A post by Richard Terrell at Critical-Gaming Network from late last year discusses set pieces, drawing on, among other things, Super Mario Bros. Terrell rightly points to World 2-3 as a distinct Mario Bros. set piece. In this world, Mario's conventional platforming is performed while flying Cheep-Cheeps move in non-normative patterns that do not match traditional enemies. Although Mario Bros. succeeds partly because each world feels unique, this level is particularly memorable because it distinguishes itself from its surroundings.

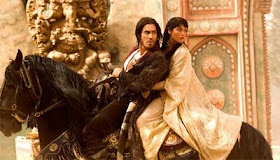

A post by Richard Terrell at Critical-Gaming Network from late last year discusses set pieces, drawing on, among other things, Super Mario Bros. Terrell rightly points to World 2-3 as a distinct Mario Bros. set piece. In this world, Mario's conventional platforming is performed while flying Cheep-Cheeps move in non-normative patterns that do not match traditional enemies. Although Mario Bros. succeeds partly because each world feels unique, this level is particularly memorable because it distinguishes itself from its surroundings.Naughty Dog expertly intermingles unique set pieces into Uncharted 2 with comparatively high frequency. In an iconic scene revealed at E3 2009, Nathan battles a group of soldiers inside a hotel, taking cover behind pillars and furniture as normal. Suddenly an attack helicopter blasts the hotel, causing it to fall into a neighboring building. For a brief moment, the floor tilts dramatically and shooting enemies becomes more difficult. Finally, jarring the player's sense of control, Nathan leaps to safety.

The collapsing hotel scene is short, but its brevity is partly why it is so memorable. For a brief moment, along with visual changes, normative gameplay is slightly altered to create a new and unique experience. This strategy is repeated throughout the game, alternatively keeping the pace riveting and relaxing. Similar set pieces include a sliding platform in Shambala, a homicidal truck in an alleyway, a tank vs. village scenario, and a truck platforming sequence. Each of these scenes stand alone, sandwiched between normal game interaction.

The truck scene, and a similar train sequence, are longer set pieces that still succeed because they adhere to the 'brief alterations' rule. The train platforming scenario is a unique set piece itself, but it is also broken up into variations on the theme. At times, players must dodge oncoming obstacles, combat a helicopter on a moving vehicle, and snipe distant enemies while correcting for the curvature of the tracks. These longer set pieces follow Hitchcock's suggestion on a smaller scale while avoiding tedium.

While less adeptly paced, Modern Warfare 2 follows the trend of set piece design with its own variations on its gameplay conventions. A brief non-traditional segment of trench warfare in front of the White House is particularly memorable. A pitch black city suffering the effects of an electro-magnetic pulse creates another memorable set piece. While Modern Warfare 2 lets some of its levels drag on (Favela, Burger Town), it is indicative of a trend towards a level design that is built around these memorable set pieces.

While less adeptly paced, Modern Warfare 2 follows the trend of set piece design with its own variations on its gameplay conventions. A brief non-traditional segment of trench warfare in front of the White House is particularly memorable. A pitch black city suffering the effects of an electro-magnetic pulse creates another memorable set piece. While Modern Warfare 2 lets some of its levels drag on (Favela, Burger Town), it is indicative of a trend towards a level design that is built around these memorable set pieces.These aforementioned set pieces are strictly linear scripted events, but they need not be. The quick downpours of Left 4 Dead 2's 'Heavy Rain' campaign is entirely controlled by the AI director. Nevertheless, its sudden alteration to existing conventions create for emergent behavior and memorable results. In a medium built upon small iterations of game conventions (not necessarily a bad thing), distinct crescendos and narrative "bumps" are powerful design tools to enliven a game and smooth its pacing. Uncharted 2 is one of the best paced games I have ever played, in no small part due to its exquisite pacing and fluid set piece integration. Building games around narrative and gameplay moments holds great potential. Alfred Hitchcock would be proud.